With only a few weeks until the start of Phish’s summer tour, I get excited and want to nerd out with the #twibe and just talk about Phish’s music. So I posed a question on twitter out of general curiosity:

Lots of great answers came in from folks, with many of my favorite ballads included: “Dirt,” “Fast Enough For You,” “Billy Breathes,” “Lifeboy.” I had a good conversation with @Mr_Completely about subjective taste and how I don’t care one bit for “Anything But Me.” But I also got some interesting replies that I initially felt were outside the genre of “ballad,” at least as far as we define it in the Phish world: “Esther,” “Tela,” “Frankie Says,” “Nothing.” And even the (perhaps) tongue-in-cheek response “Lengthwise” left me thinking “well, maybe that IS a Phish ballad!”

So…what do we mean when we say Phish ballad?

The answer, of course, is tenuous and subjective, and every phan is free to entirely disagree with me on these points. Yet when we use words like “ballad” or “anthem” or any other number of genre designations, we are discursively engage with a term that spans many types of music and sometimes many centuries of Western thought.

Historically, the term ballad has meant many different things to many different cultures, and even within those cultures, it has meant different things at different times within different styles of music. Etymologically speaking, the word is derived from the Latin “ballare,” or “to dance.” Indeed, the ballad in medieval Europe was initially a song that accompanied a French dance. The French “ballade” was a fixed song type that dominated French secular song and poetry in the 14th and 15th centuries, while England had a 17th-century comic genre called “ballad opera.” We can start to see the literary nature of the term ballad, the idea that the words of the song are as much a governing part of the genre as the text.

The “folk ballad” was increasingly a song that told a long narrative story. In fact, the scholars who first started talking about ballads were more interested in the stories and formal structure of the texts—the tunes could even vary for a single ballad text! Music was just the vehicle for getting the story told. As such, early British examples are mostly strophic, meaning that every poetic verse uses the same repeating music. That doesn’t make for particularly exciting songs, but it does focus the listener onto the lyrics, since you don’t get distracted by the music in any way. A great example of these early ballads is “Cruel Sister,” which dates from probably the 18th century and was popularized by the British folk group Pentangle in 1970.

As you can hear from this version, the music to each verse is the same, although Pentangle at least keeps adding instruments to every verse, offering some variation (love that sitar!). But the elements are all there: long storytelling, an impersonal narrator, strophic form. Tempo isn’t so much a consideration, but the songs needed to be slow enough so that listeners could understand and follow the story. Starting in the 17th century, ballads were also forms of social commentary, a thread that the American folk movement of the 1950s and 60s would pick up.

So that’s the origin of the term, but what about its modern usage? As with so many musical ideas and terms, today’s ballads take a little from a variety of different musical traditions. The ballad became really popular in America via Irish music in the 19th century, which basically influenced all American popular music. Songs like “Kathleen Mavourneen” were distributed on broadsides, basically posters, so that people could sing them at home. This was also how a lot of ballads came to be known in writing—previously, many ballads were simply taught via oral tradition.

So that’s the origin of the term, but what about its modern usage? As with so many musical ideas and terms, today’s ballads take a little from a variety of different musical traditions. The ballad became really popular in America via Irish music in the 19th century, which basically influenced all American popular music. Songs like “Kathleen Mavourneen” were distributed on broadsides, basically posters, so that people could sing them at home. This was also how a lot of ballads came to be known in writing—previously, many ballads were simply taught via oral tradition.

Since so many of these ballads were also sentimental songs, increasingly the ballad became a song of love, loss, death, nostalgia, and other deep human emotions. The narrator became less impersonal, the tragedy of the tale belonged to the lyrical self. This was especially true after the Civil War, when Americans craved a way to deal with their national grief and pine for the antebellum simplicity of American life. Notably, ballads weren’t used for dancing anymore, at least not the popular dances like waltzes, quadrilles, lancers, and so forth. By the early 20th century, Tin Pan Alley had taken control of American popular music, incorporating the ballad as a song type usually about love (sometimes lost). And since so much popular music was again for dancing in the wake of jazz and the popularity of broadway, the slower songs all gradually became known as ballads. The narrative ballad of the 18th century merged with the sentimental song or love song of the 19th century and became, in the 20th century, a new kind of ballad.

In the jamband world, the term “ballad” has its own history and tradition. The Grateful Dead have many ballads, but because the band members were huge folkies in the late 50s and early 60s, many Dead ballads harken back to the older idea of a narrative story told in simple forms. You end up with death ballads (“Black Peter”), murder ballads (“Jack Straw”), and hybrid love/death ballads (“Wharf Rat”). And of course you get slow love songs that, like the love songs of Tin Pan Alley, jazz, and early rock n roll, were called ballads (“Looks Like Rain”). But “Jack Straw” is fundamentally a different musical animal than “Black Peter” or any of the dozens of other Grateful Dead ballads. It’s got a relatively complex form with contrasting sections, and most importantly, it’s a fast rock tune (at least, fast by Grateful Dead rock standards). However, it is unmistakably a part of the ballad tradition, even though very few Deadheads would ever call it a ballad.

Increasingly, the “ballad” became the term for the slow song that Jerry would sing late in the second set, after Drums>Space and usually just before the closer. Because the Dead were so well versed and steeped in the traditions of American song, and because Hunter was so well read, almost all the songs that Deadheads call “ballads” in the Grateful Dead songbook have clear connections to the historical genre. They all deal in some way with love, loss, or death.

To be honest, I can’t think of a single slow Dead song that doesn’t share some characteristic with the traditional ballad, whether in its strophic narrative structure (“Lady With a Fan”), its focus on death (“Days Between”), or topics of love (“Standing on the Moon”) and/or sadness (“To Lay Me Down”). Hell, even “Friend of the Devil,” a bluegrass tune derived from the murder ballads of the blues, got slowed down in the late 1970s, as if to accentuate its newfound identity as a ballad.

So now to Phish. What makes a Phish ballad? Clearly there are the songs that fall into the previously enumerated categories and styles: love songs (“Waste”), songs about loss (“Dog-Faced Boy”), and love/death hybrids (“Joy”). And those are all at a slow tempo, with typical verse/chorus forms, true to the conventions of the genre in the 20th century. Yet the themes of many Phish slow songs are often of an existential variety, in large part because of the nature of Tom Marshall’s writing. It’s tough to say exactly whether “Strange Design” or “Dirt” or “Mountains in the Mist” are sad songs, or love songs, or songs about God or fame or the modern condition or what. There’s often a “you” in these lyrics, but it’s not always clear that the “you” is the object of a romantic relationship. That’s part of why we love them, because we can graft our own conception of “you” onto these shells. “Shout your name into the wind” is a gorgeous image for the affection of a loved one, but the metaphor of “Dirt” is of the narrator withdrawing from the pressures of the world and, because of that, will “never hear your voice again.” And since being buried in dirt most often happens when we die, is it a song about death?

I would say that all those songs dealing with life’s heaviness in the last paragraph—plus “Fast Enough For You” and “Lifeboy” and “Swept Away/Steep” and “All of These Dreams” and “If I Could” and “Billy Breathes” and a few others—are all ballads. Of course there are plenty of slow songs in Phish’s repertoire that I would be hard pressed to call a ballad, “Ghost” being probably the most obvious, or “Prince Caspian” or “Theme From the Bottom.” Yet there are other slow Phish songs that are closer to the traditional ballad in musical style, like “What’s the Use?,” that I would also be reluctant to call a ballad.

Tempo is clearly not the defining characteristic of a Phish ballad in the same way that it was for the Dead. Phish ballads are also structurally conventional forms, at least as derived from the jazz/Tin Pan Alley/rock ballad. They are all verse/chorus songs, some with a bridge, some with a big ending guitar solo (perhaps a leftover of another bastardized genre, the power ballad). And for the most part, they travel in the well-trod harmonic and melodic language of rock and Tin Pan Alley popular song. There’s not a ton of jazziness or odd proggy harmonies full of dissonance and chromaticism. That’s not to say that there aren’t some really interesting harmonies—“Billy Breathes,” for example, features a chord progression that starts on the VI chord, which tricks your ear into hearing that as the tonic and allows for some interesting harmonic effects—but the chords are mostly diatonic triads, devoid of flat 5s and extended 7ths and 9ths.

One category of Phish song that some people called ballads in response to my tweet have a quiet dynamic level and often have a gentle rhythmic feel, both of which belie their relatively fast tempo. Moreover, these songs often use elements that we associate with musical psychedelia, such as modal writing rather than chordal, phase-shifted or otherwise altered timbres, and non-traditional song forms. In my opinion these songs are not ballads, they fall into their own category of slower psychedelic songs. It’s certainly possible to have a psychedelic ballad: Pink Floyd’s “Fearless” or the Allman Brothers Band’s “Dreams,” or even the Dead’s “Wharf Rat.”

But consider a Phish song like “Waves.” The song plays around with A mixolydian and while there are chord changes, there is no sense of goal-direction and arrival like there is in other Phish ballads. Even the one moment where arrival seems to occur, the transition between the bridge and verse (“and possibly won’t reach her ear”), it’s avoided. The harmony sets you up for a cadence in D major, but instead, you just keep floating on that A mixolydian riff. The structure of the song, too, is ephemeral, built on these aphoristic two-line verses separated by the same sets of riffs, and then a contrasting B section. But there’s no refrain, no chorus, no big harmonic or structural changes to signify development. Is “Waves” a ballad? Despite it’s relatively subdued feel, I’d say no.

In that boat, I’d add a song like “Frankie Says,” another song with a deceptively fast tempo hidden by an effortlessly lilting drum part and quiet dynamic. That’s contrasted with a song like “Roggae,” which has a similar psychedelic character, but has a verse/chorus form and goal-directed harmonic progression built on triadic chords. “Roggae,” I’d argue, is a ballad, even though many of us think of it in an entirely different category than, say, “Velvet Sea.”

Then there are a few outliers. “Tela” was Phish’s only slow song for nearly the first ten years of their existence, until they debuted “Fast Enough For You” in the fall of 1992. As Trey wrote in his thesis, he composed “Tela” specifically because it was out of his comfort zone, and it was the first song he ever wrote with someone else’s vocal (Page’s) in mind. So the song was consciously divergent from other Phish tunes at the time. “Tela” could easily be called a ballad: it’s slow and it’s a love song, perhaps it’s Phish’s most explicit love song other than “Waste” or, lyrically, “My Sweet One.” But there are some anomalies. The harmony is quite complex, with a sus4 chord, a minor 7th flat 5 chord, a ninth chord, and lots of mode mixture (which has a chromatic effect, for instance, switching from A major to A minor the C-sharp drops to C-natural). Those extended chords, along with the shuffle beat Fishman plays and the angular vocal melody all give the song a very jazzy feel, taking the tune outside the purview of the typical rock ballad.

The form of the song is also complex and atypical, it’s what theorist Brad Osborn would call terminally-climactic. There’s an instrumental introduction, verses, an instrumental B section, and then a big shift in key, feel, and affect as the song moves into its final section (“Tela, Tela, jewel of Wilson’s foul domain”). Now we’re in D major instead of A, the chords are all triadic and highly goal-oriented, but there’s just the one lyric and then a furious composed guitar solo. For me, “Tela” is a little too complex and atypical to be considered a ballad, in part because the ballad is such a standard song type, and therefore too much deviation from the genre makes it unrecognizable as such. Similarly, even though “Lengthwise” is a love song, slow, and strophic, it’s just too much of an oddity, a curiosity, to be a ballad.

Genre theorists talk about the idea of a “generic contract” between the musician and the listener. “Ballad” denotes a number of attributes that we should expect, but as an audience we have to allow for some deviation from and flexibility within those expectations. That’s what makes good music. But we can be confused if the music veers too far. In the case of Phish, I’d argue that confusion is something that we really value; we like Phish in part because it’s difficult to categorize their music into a genre per se. Yet the ballad is perhaps the one type of Phish song that does conform to genre expectations more than others. That may be one of the defining characteristics of a Phish ballad: it doesn’t sound like it could only be Phish.

Two final examples.

“Esther” is a story song that, lyrically, is very much like the old narrative ballads. It’s a semi-fantastical, supernatural tale. And it’s relatively slow, although like “Waves” and “Frankie Says,” its tempo is actually faster than you think because the drum part is quiet and gentle and there’s no backbeat. But “Esther” is too through-composed, like a prog rock song, to be a ballad. Like “Tela,” its harmonic relationships are complex and based on dissonant or chromatic relationships, and its structure is idiosyncratic: it sort of goes ABCDB, where A = “it was late one fall night,” B = “Esther tried in vain…” + composed piano/guitar solo, C = the flying jam, D = the nasty part of town, and then the final B = “When the morning came” + final guitar solo, which itself is a variant of the earlier solo.

Finally, could there be an instrumental ballad? Historically it’s happened: Chopin wrote four “Ballades” that were intended to be solo piano adaptations of the epic narrative ballads, and there’s always the iconic “Sleepwalk” by Santo and Johnny, a.k.a. the song that plays at the end of La Bamba (spoiler alert: it’s the day the music died. Bye bye miss American pie).

I’ve dismissed “What’s the Use?” partly because of its psychedelic quality, and yet especially in the way it’s been played in 3.0 shows, it does have the other musical hallmarks of a ballad: goal-oriented triadic harmony, contrasting sections, and while there are no lyrics, the title conveys an existential crisis while the music has both sadness and hope. Its form is a bit anomalous to really be a ballad, but it’s close. Yet I’d argue that “I Am Hydrogen,” one of Phish’s earliest songs, is in fact a ballad. It’s got a verse, a contrasting B section, it’s slow, and it has the goal-oriented harmonic plan, albeit there’s a big chromatic section in the middle. Still, even that proggy touch merely serves as a transition from the B section back to the A.

This is all to say that none of this really matters at all. It’s just something fun that I thought about writing, and I haven’t blogged about Phish for a while. So feel free to engage and disagree or ask a question, I’m happy to talk endlessly about this stuff. After all, summer tour is just around the corner! Take me to another time…

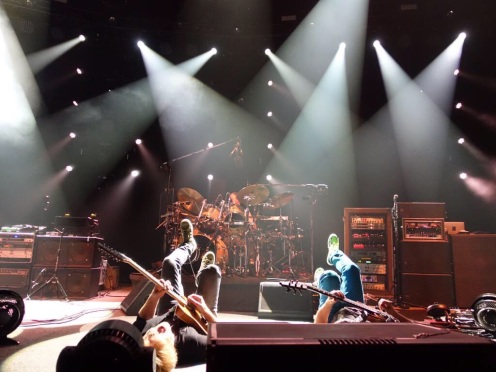

What a way to get shut out of a show! Back to my original point: there was very little darkness for these shows. The second set opened with the sun setting, and only during the meat of the second set was there enough dark for CK5 to really get to work on his smaller, venue-resized rig. This was really apparent on the second night, as the second set opened with three quite mellow but unbelievably beautiful tunes: “A Song I Heard the Ocean Sing”->”Waves”>”Wingsuit.”

What a way to get shut out of a show! Back to my original point: there was very little darkness for these shows. The second set opened with the sun setting, and only during the meat of the second set was there enough dark for CK5 to really get to work on his smaller, venue-resized rig. This was really apparent on the second night, as the second set opened with three quite mellow but unbelievably beautiful tunes: “A Song I Heard the Ocean Sing”->”Waves”>”Wingsuit.”